[This post originally appeared on

ReformJudaism.org]

This week, as we begin the Book of Leviticus with

Parashat Vayikra,

we read about the eternal flame in the Temple in Jerusalem — a symbol

of God’s Presence amidst the Jewish people. The smoke rising from the

altar was a remnant of our communications with God — physical evidence

that we had engaged with the Eternal.

Cantor David Berger writes that “As moderns we have fully embraced

the transition from Temple service to ‘the service of the heart,’”

citing Babylonian Talmud,

Taanit 2a:

To love the Lord your God and to serve Him with all your

heart” (Deut. 11:13). Which is the service of God that is performed in

the heart? You must say that this is referring to prayer.

We could take this to mean that as we no longer make physical

sacrifices, rather than serving God with our hands, we serve with our

hearts and minds. And yes, we have transformed Judaism — the work of our

hands, turning substance into flame and smoke became the work of our

minds, turning words into music and praise. But where does that leave

our hands? I suggest that we still have the power — and the

responsibility — to serve God with our hands.

The altar smoke — “of pleasing odor to the Eternal” (Lev. 2:9)

— is akin to a finished work of art created by a painter or sculptor.

It is the lingering echo of music after an orchestra plays or the warmth

of a room that has been filled with dancers exercising their bodies. A

painting is the evidence that we have painted — and art about the Jewish

experience is evidence of our efforts to commune with our people across

time, and with the Divine.

The Jewish-American artist Barbara Kruger said, “Making art is

about objectifying your experience of the world, transforming the flow

of moments into something visual, or textual, or musical, whatever.”

When we use the work of our hands in concert with the work of our minds,

we can transform our personal experience of the world and the Divine

into a shared moment — into a part of the continuing conversation that

has been part and parcel of Judaism since the Divine creation of the

world.

Our history reveals a continuous connection between art and Jewish

practice — from the carving of the Ten Commandments in the moments

before the first Shabbat at the end of Creation (

Pirkei Avot 5:6) to Bezalel leading the Israelites in the building of the desert

Mishkan (Ex. 35), to the commandment of

hiddur mitzvah, “beautifying the commandments.” In

Midrash M’chilta d’ Rabbi Ishmael,it says:

“I shall glorify God in the way I perform mitzvot. I shall prepare a beautiful lulav, beautiful sukkah, beautiful tzitzit, and beautiful tefillin.” (Shirata,

Ch. 3). The Talmud adds, “a beautiful shofar and a beautiful Torah

scroll which has been written by a skilled scribe with fine ink and fine

pen and wrapped in beautiful silks” (Shabbat 133b).

Our hands still can — and must — do the work of connecting us to the

Divine. We can paint, draw, weave, cut, carve, and inscribe — in the

service of our people and the Eternal. We can tell our story, praise

God, and promote the ideals of

tzedakah,

emet and shalom.

|

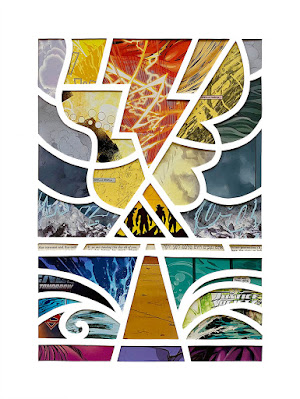

"Altar Flame" and "Altar Smoke"

[click to enlarge] |

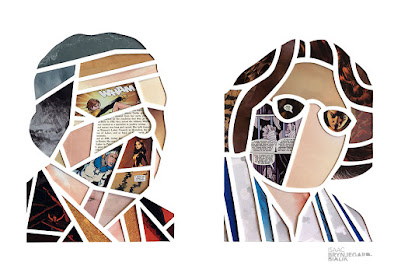

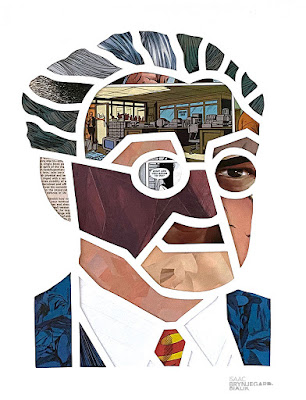

In my work as a papercutter I am in constant engagement with this

task, cutting up and collaging comic books and other found materials and

using them as a lens through which to study Torah and make “paper

midrash.” My papercuts “Altar Flame” and “Altar Smoke” are two

explorations of this week’s

parashah: attempts to find meaning in superseded ritual practices.

Both of these papercuts reflect the connection between the Jewish

people and the Divine, in ancient and modern practice. Within the flames

rising from the altar can be found Phoenix, a superhero member of the

X-Men with godlike powers, as well as Wonder Woman, whose story is one

of constant back-and-forth between gods and human beings. Tucked into

the sacrificial smoke are comics featuring godlike heroes like Superman

and Thor and also very human heroes like Batman. Our narratives about

the relationships of these super-powered beings, and how they connect

with the people around them, an inform our ideas about our relationship

with God. We ask ourselves what it means to communicate directly with

the Divine, and for what purpose we praise God with our hands and

hearts.

Jews have always made things of beauty — for ritual and observance,

and also to inspire people and praise the Divine. The work of our hands

is vital to the work of our souls.